Although nature does not care where one species ends and another begins, humans have always categorised and named the natural world to make sense of it. The way research is defined and the way knowledge is shared, is strongly embedded in our culture and our values concerning the natural world. At Waag’s TextileLab we challenge a merely mechanical, reductionist and objective approach to research. We ask ourselves if we can do research in a more holistic way and further, if we can embrace and value a sense of wonder, intuition and care in our research?

This approach is visible in the Local Color project. At its core Local Color operates as an exploration into the city as an enabling environment, adding a layer of functionality to public spaces by transforming green urban areas into dye gardens for local production. This project is driven by an impulse to produce natural pigments in our urban environment and create a local value chain. Also in Local Color we research, categorise and name biochromes (colours coming from natural resources) that can be found in the city that might be part of the local value chain we are uncovering. On the 18th of January 2024, Local color hosted a public meet up called The need to name and the stories we tell. During this meet-up four plant researchers gave presentations about their work with a strong emphasis on the cultural context in which their research is embedded.

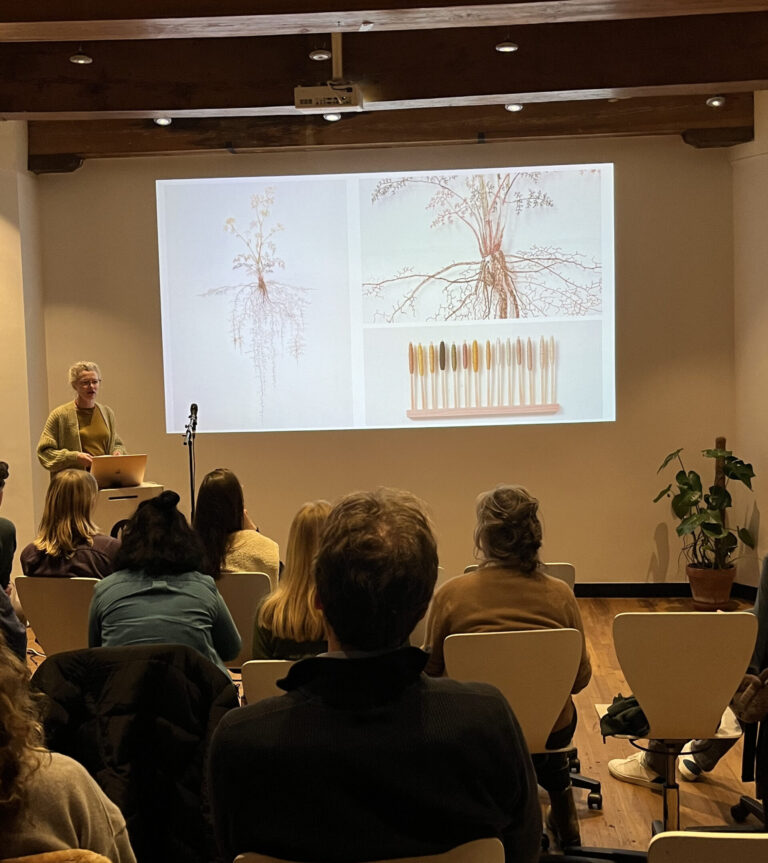

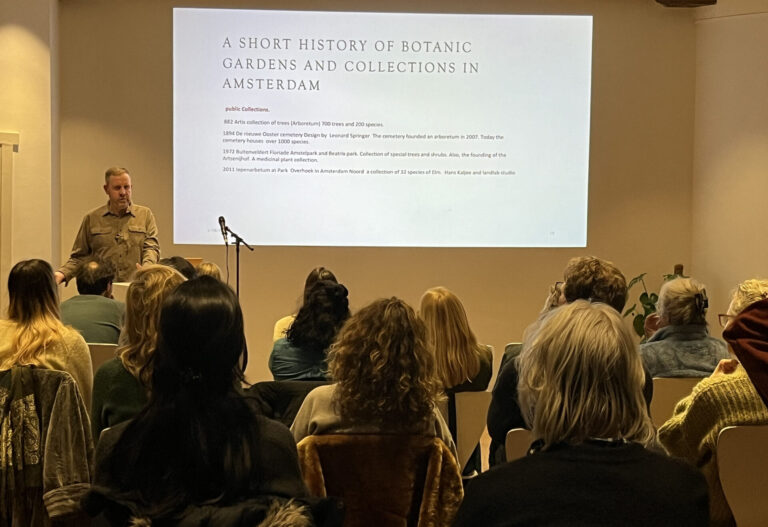

Plant enthusiast Maarten van Bodegraven started with a presentation about the origin and function of botanical gardens in the city throughout the centuries. Creative researcher and natural dyes specialist Cecilia Raspanti talked about the importance of creative taxonomies to understand the world of possibilities and about the needed attitude of a researcher. Plant philosopher Norbert Peeters spoke about our (changing) ideas concerning plants we consider weeds, focusing on words such as ‘native’ or ‘exotic’. Doctor and artist Marjolein Hessels showed how different ways of doing research merge in her work and stressed the importance of care when working with the natural world.