“Dyeing with plants is a beautiful and old craft. We should approach it with respect for those who have gone before us.”

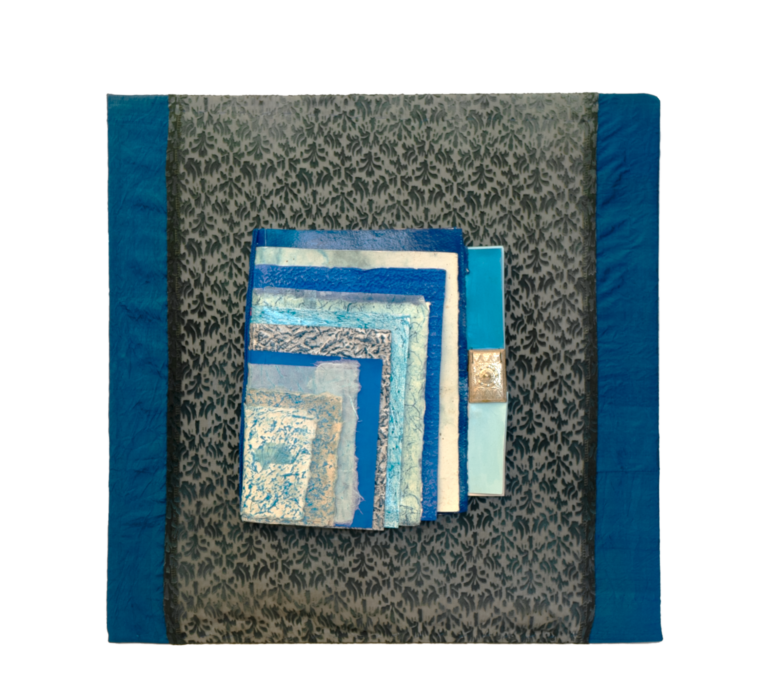

If you take a walk around the Nieuwmarkt and look very carefully, you might be able to catch glimpses of the textile industry that once bloomed there from the 16th century up until the Second World War. The ‘Staalstraat’ street, for instance, which many assume has something to do with steel, was in fact named this way because of the ‘Staalhof’, and the ’Staalmeesters’ (Sampling Officials) who worked there. These officials used textile samples (‘stalen’) to inspect and grade the quality of the textiles on offer. Other examples are the ‘Verversstraat’ (Dyer’s Street) and the ‘Raamgracht’ (Frame Canal) which refers to the frames on which textiles were stretched after they had been washed and dyed. Artist Heleen van Deur investigated this rich history through art. In her work ‘Uit het stof gehaald’ she explored 32 professions that once lay at the heart of the textile industry.

When I ask Heleen about what drew her to study the crafts on the Nieuwmarkt. She responds emotionally:

“I have boundless respect for the people that used to work here. I was drawn to these people, because they had terribly difficult lives. I sometimes think we should be happy that all these crafts have disappeared. The dyers, for example, stood in filthy pools of muck and urine up to their ankles to get the dye onto the textiles. Yet at the same time, there is enormous beauty in craftsmanship. Why do I get so emotional about this? Maybe because crafts are so underappreciated. Especially in the arts. And that despite the fact that historically arts and crafts have always been so closely intertwined.”

Heleen explains that these crafts were not carried out in isolation, but were co-dependant on one another. Bigger operations were often subdivided out into separate tasks. Some people only unpicked thread or removed pilling from textiles. She talks about how various crafts and techniques were brought in by migrant groups, and thus how this industry became a place where artisanal traditions intermingled. Heleen is acutely aware of the differing social statuses of and within these professions, and speaks reverently of the role of the Jewish community in the textile street trade. She explains how Jews were excluded from joining the guilds and thus often had to restrict themselves to trading second hand goods on the market. Rag sorting, for example, was a classically Jewish profession. Rag sorters would collect and sort discarded rags and worn out clothing, sometimes for reuse, but most often to be broken down into a pulp for making paper.

Having seen the works of Heleen, it is impossible to ignore the magnitude and diversity of the various professions and crafts that made up this once thriving textile industry. I ask her what she thinks would need to happen for a technique like plant dyeing to be brought back to life, in more than just an experimental way. She recalls a time she visited the ‘Stedelijk Museum’ with a friend (a professor of agriculture). I once visited the ‘Stedelijk Museum’ with a friend of mine (Louise Fresco, professor of agriculture).

“In this museum there were some beautiful examples of dyeing textiles, and I was very lyrical about them. My friend is quite sceptical about such possibilities. She responded to my lyricism in a very rational way: ‘You don’t really think that we could do this at a bigger scale?’ she said. The current reality is that if you want a piece of clothing that looks good, and will last a long time, it will cost a thousand euros. Well, perhaps the elite will happily spend that money, and perhaps the Rue de Montagne will gladly try it. But the rest of the public will go to Zara or H&M and buy something that looks like it for a tenner. So, our visit to the museum put me back on earth. But I nevertheless think that these old, extinct crafts need to be described well.

Heleen’s anecdote is a relevant one. It makes me think. There seems to be a tension between experimentation with natural dyes, and the existing norms and expectations regarding clothing. Whenever the word ‘scale’ is mentioned in the clothing industry, we tend to think of large corporations like Zara and H&M. These companies have, regardless of intention, changed what we expect of clothing. One example of this is repair. In the Netherlands it was once very normal to repair clothing and wear repaired clothing. But such companies have made garments so cheap that it is not worth people’s time to repair them. You might as well buy a replacement. And so, over time, our repair practices have eroded. Which in turn has made it normal to produce and buy unmendable clothing. We’re not surprised if we see such irreparable clothing on the shelves now.

The same goes for the way colour has disconnected from its sources, and become something we simply expect to have a broad choice in. As Heleen demonstrates with her work ‘Blauwverver’, the colour of a textile in 16th century Amsterdam used to bear significance by virtue of how difficult it was to make. Recipes were kept under lock and key. Some colours were much more valuable than others. This also meant the elite were able to flaunt their wealth by wearing certain colored clothes. Nowadays, since the advent of synthetic dyes, the existence of such ‘expensive colours’ has faded. But with this fading has also come the expectation that clothing should be available in almost any colour imaginable. We can question whether that is a desirable norm.

In the same way such corporations have, through their production lines, changed the meaning of colour, they have also shaped our understanding of what it means to ‘scale’ in the textile industry. So, if we want to talk about how techniques like plant dyeing might be ‘scaled-up’, we must take care to examine what we mean by that word. Which scaling practices are implied? Which expectations and norms around clothing are taken for granted and thus reinforced? For large corporations that need to protect their market share, it makes sense to only stimulate and invest in dyeing processes that have the potential to scale-up to the extent that they might replace existing processes. But if our idea of ‘scaling-up’ only allows us to look for one optimal way of doing things, we risk ignoring a wealth and diversity of dyeing processes. Scaling in this way would never allow for multiple dyeing techniques to exist at once.

Heleen ends her anecdote by insisting that old crafts must be described and documented well. For a project like Local Color, such documentation and artistic engagement with history could not be more valuable. Historical accounts of textile industries allow us to make comparisons with the way things are today. What was good, what was bad? And how should we approach the future?